1950s Christmas

I can remember the rancid smell of black rubber buckled boots, a size larger than my feet, drying out not too close to the oil burning stove in the living room. I can remember the sizzling sound of melting snow from mittens placed briefly on top of that same furnace, then tossed next to the boots for drying.

I can remember the taste of a green woolen scarf, not meant for a child’s head, tied under my chin in a big knot. The knot’s edges reached up next to my mouth. In the winter air, moistened by the condensation of my warm breath, they would stick to my lips. I spit the edges out, but the taste of the wet wool remained.

The smells, the sounds, and the unpleasant tastes didn’t matter. It snowed, and what we had to wear didn’t matter. What mattered was we had a sled, and the hill on which the Adkins Place stood, awaited.

1950’s December, in the small town of Parkston, South Dakota, the joy of the Holidays was beginning.

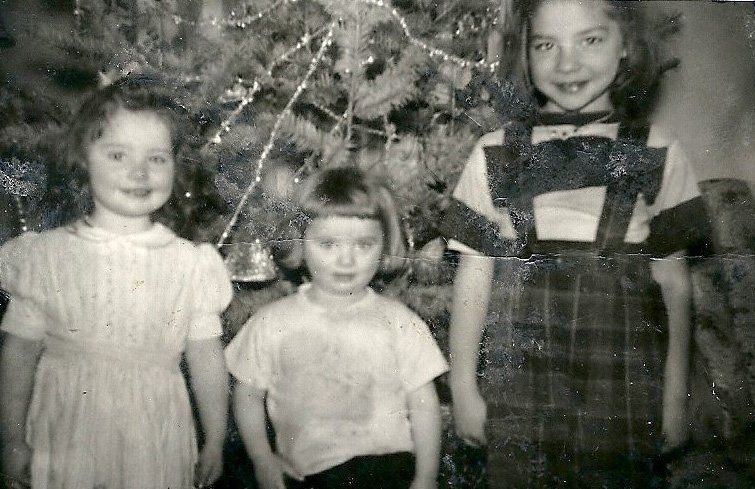

Background picture, Adkins Hill. Circa 1954

We were the third generation of Adkins to live in the house on the hill.

By the 1950s, over forty years of our family’s Christmases had been spent there. The tree was probably placed in the same spot, year after year, in front of the big living room window with the stained glassed border.

As a child, that’s where I remember it stood.

On the Adkins porch, backrow, l-r: Jim, Pete, Margaret Mize Adkins. Front, l-r: Kay, Gloria, Diane Adkins. Circa December , 1953

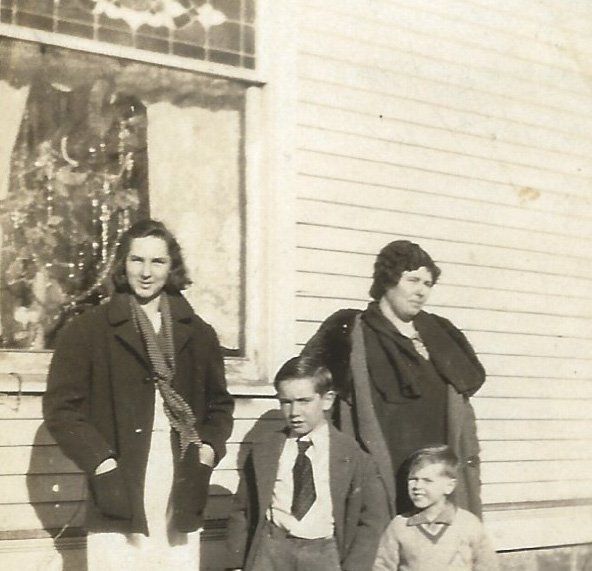

By the Adkins home window, l-r: Margie Adkins, Kenneth and Jim Stirling, Dottie Adkins Stirling. Circa 1930s

In front of the Adkins home, l-r: Hiram, Wilma Adkins, George Mattas, Margaret Mize Adkins, Vina Adkins, Grace Adkins Mattas, Grandma Ryder, Helen Adkins, Leo Koenig, Pete Adkins. Front: Jim Adkins and Charles Koenig. Circa 1938

In December, the “for sale” trees were propped against store fronts that lined Parkston’s main street. They were fir trees with some gaping holes between the branches. It was what was available then, but they smelled wonderfully. My dad, Pete, always brought the tree home. Getting the biggest he could, sometimes he had to cut part of the bottom off to get it into the house.

Placed in a pail of sand, keeping the Christmas tree upright presented its challenges. The lights were heavy, the tree maybe not the straightest. One year, Daddy, frustrated by these challenges pounded a nail in the living room ceiling and tied the tree up to it with twine.

Another year, Daddy covered the tree’s imperfection with “angle hair.” All the rage in the 1950’s, “angel hair” was spun glass that you could drape around the tree for an ethereal affect. He had to wear rubber gloves to do this. It looked pretty, but turned out to be a prickly product that plagued us through the holidays.

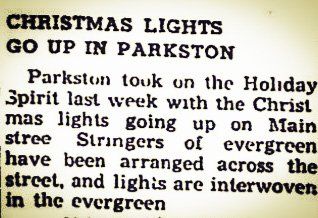

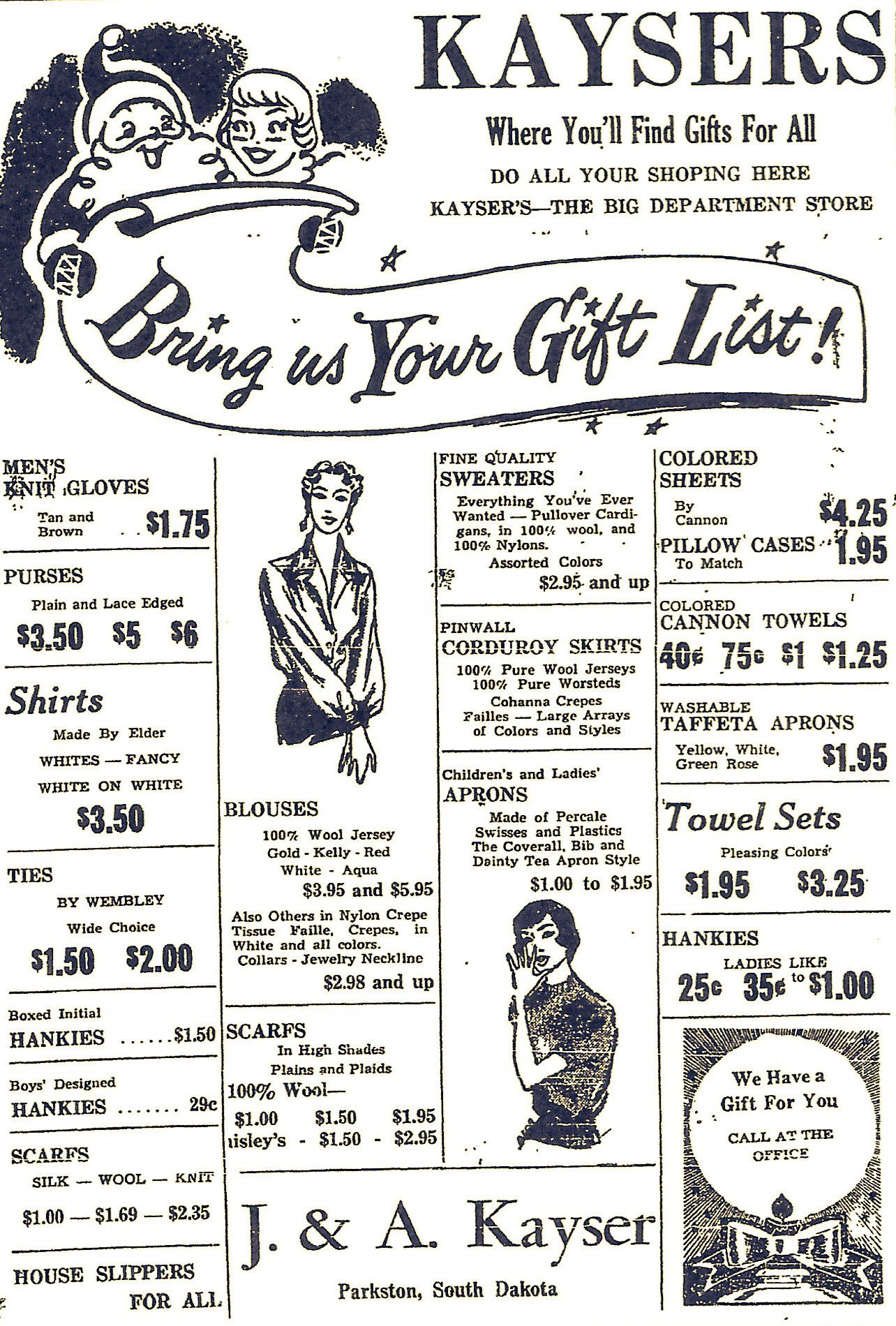

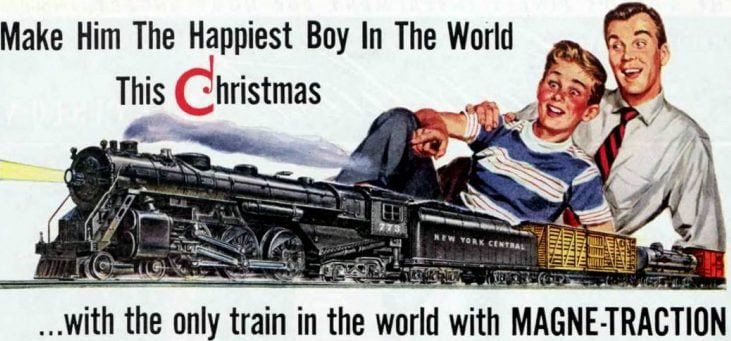

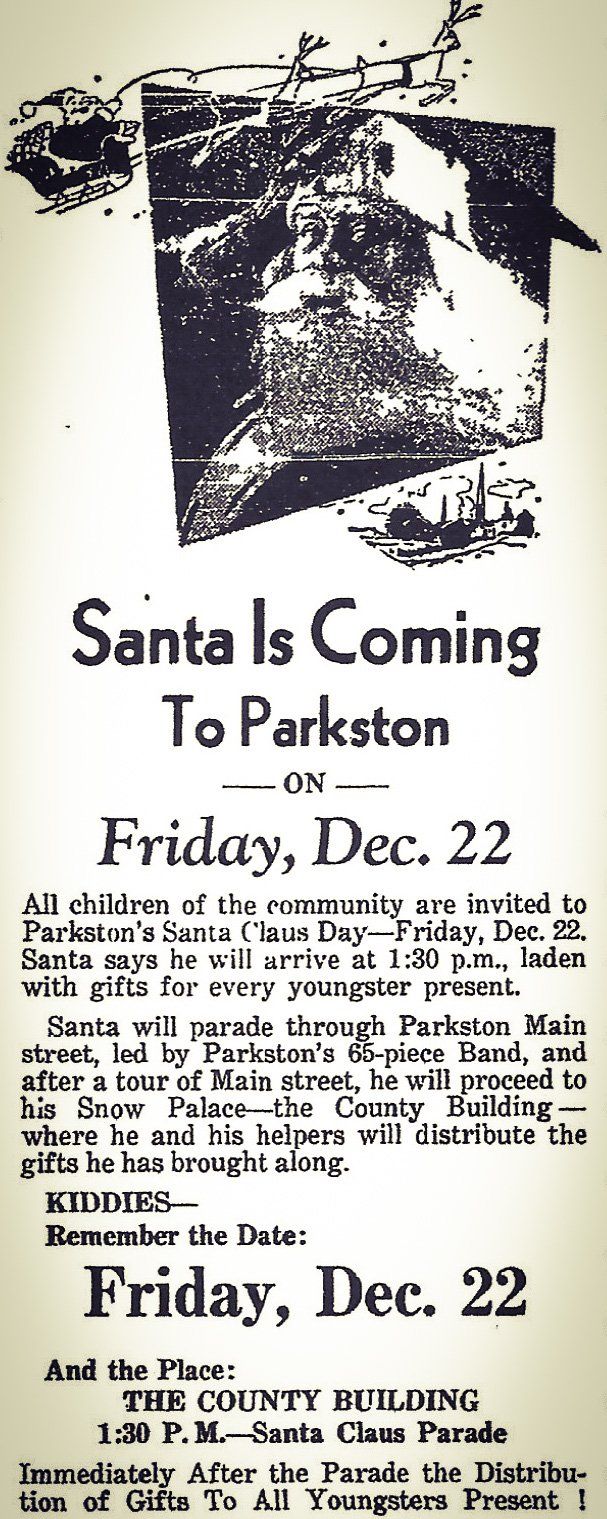

Advertisements and articles from the Parkston Advance and the Lionel Train Company. Circa 1950s

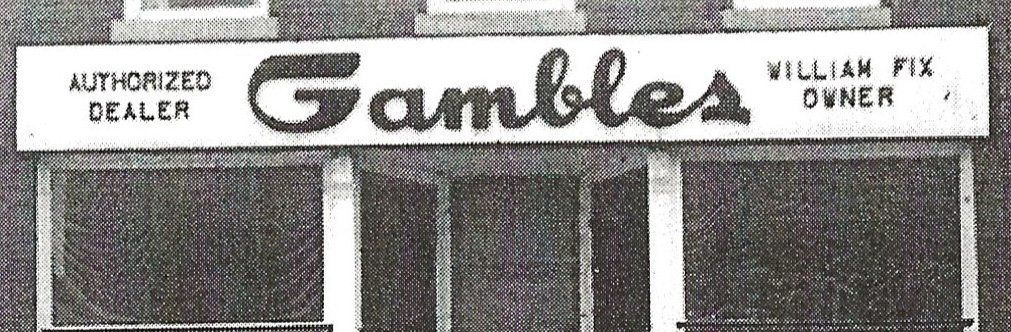

The “for sale” Christmas trees were not the only things that brought people to Parkston’s main street in the 1950s. Evergreens and lights were strung above the street from building to building. Main Street boasted many places to shop, including hardware stores, department stores, clothing stores and three groceries.

The best store for me was Gambles. In December, the owner, Bill Fix turned his second story into “Toyland.” Well behaved children could go there alone and see the marvels of electric trains - my favorite wished-for toy as I got older. I never got one, it wasn’t deemed a “girl’s” toy. My friend, Ricky Doebner did get one however, and we shared “engineer” duties. He even let me put pellets in the smokestack to create billowing clouds.

Everett Mize. Circa 1950s

The thing all of us kids waited for was Santa coming to town.

We got bags of candy and a chance to meet him in person at the County Building.

Sometimes we waited in long lines. In 1953, 1,100 of us showed up!

One year when I meet Santa, I thought I recognized him.

“You look just like my Uncle Everett," I said.

Santa leaned forward and whispered in my ear, “Santa can be anyone!"

Hutchison County Building, Parkston, South Dakota. Circa 1950s

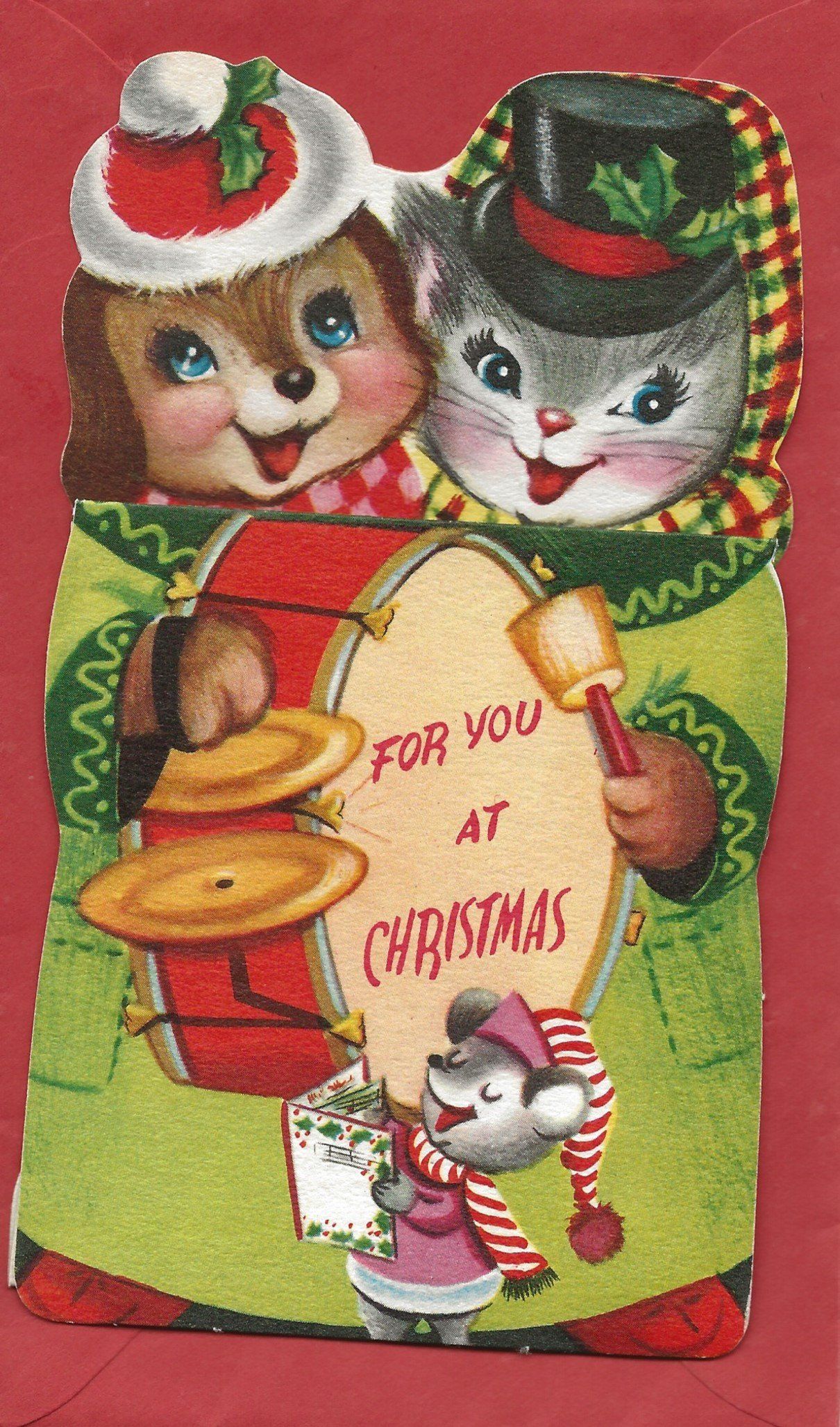

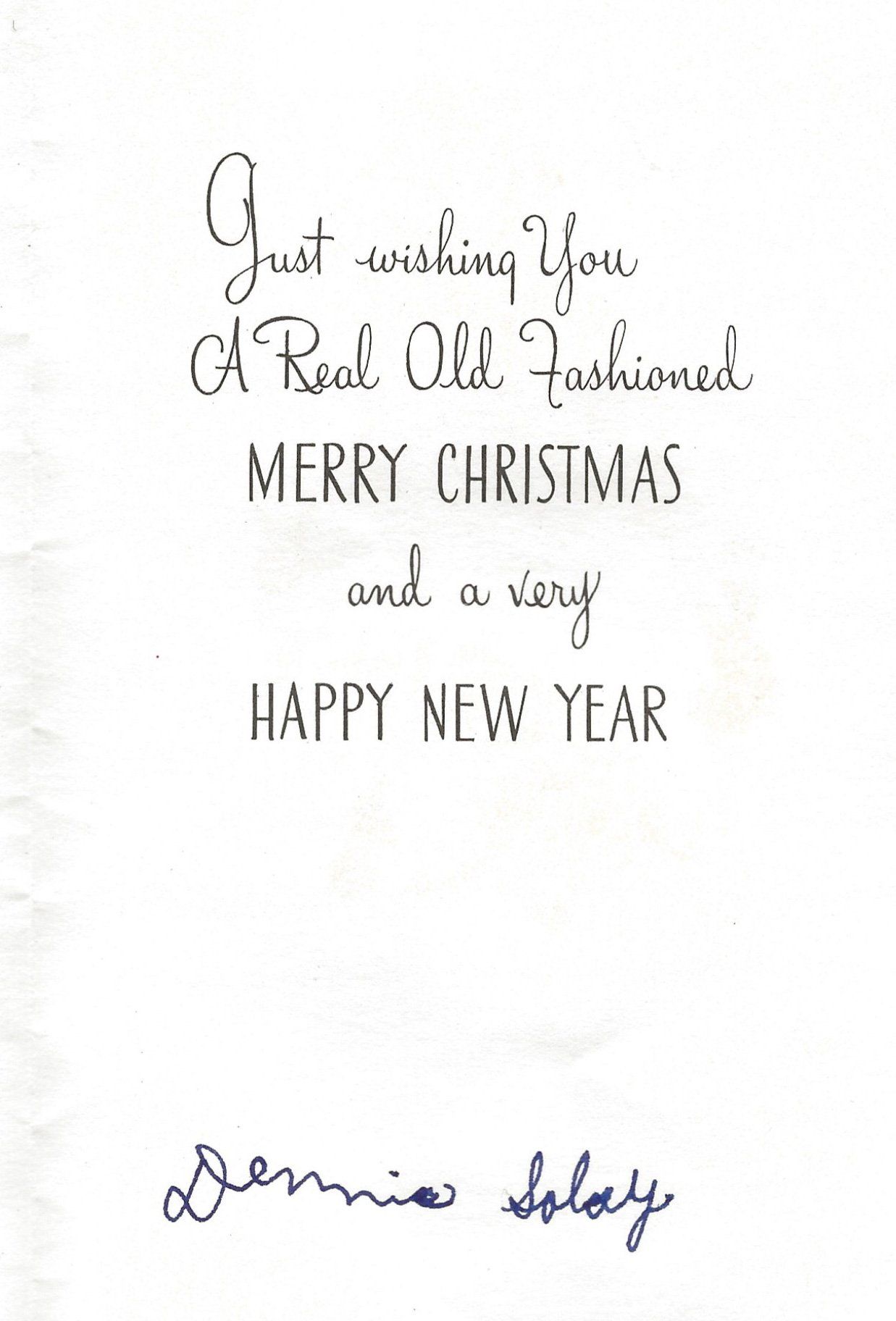

There were only 12 of us in my grade school class. It cost 2 cents to mail a Christmas card. I was delighted when I got one from my classmates.

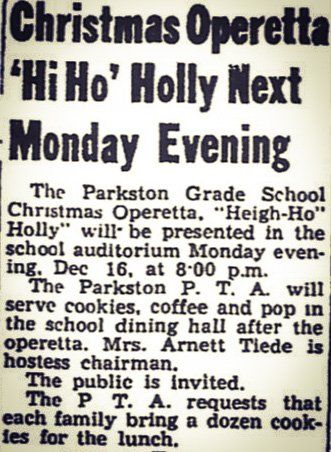

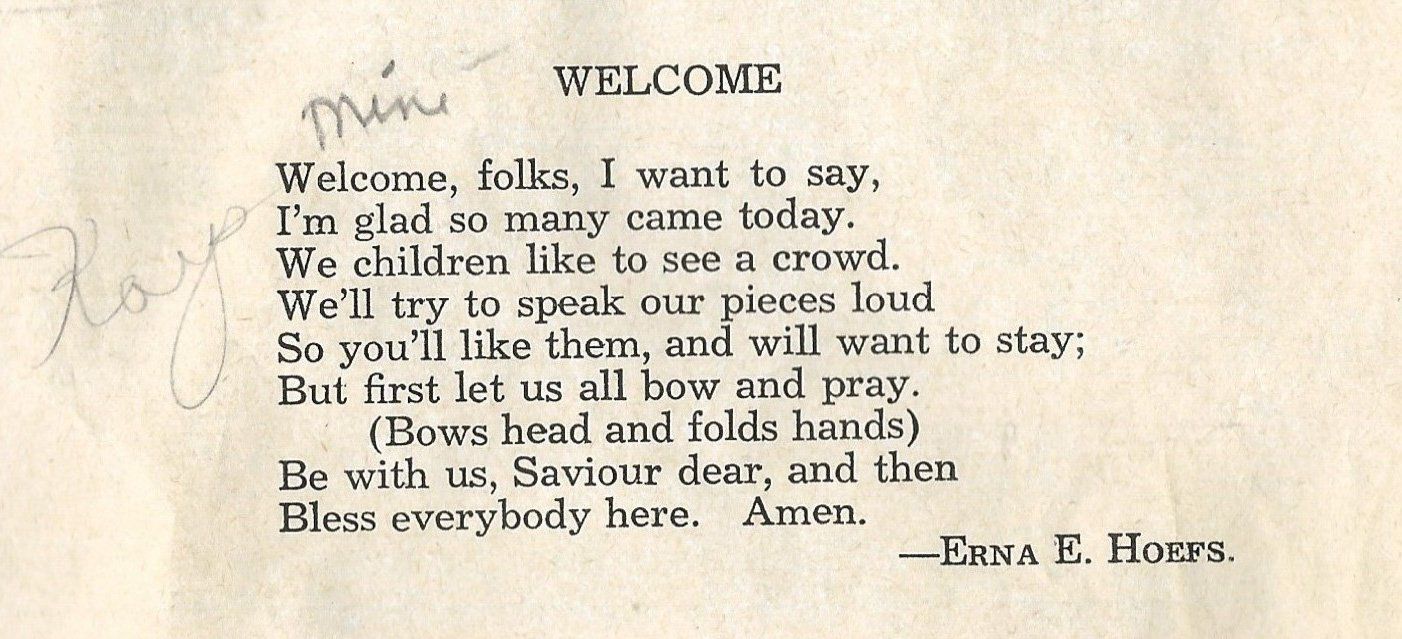

Not only did we share a classroom, we shared the annual school holiday production.

From the Parkston Advance, 1957

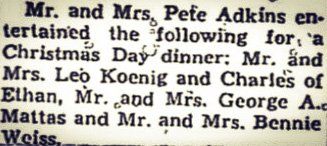

The holidays were filled with family gatherings and feasts!

Back row, l-r: George Mattas, Margie Wiess, Grace Mattas, Benny Wiess, Joyce and Leo Koenig. Front row, l-r: Jim and Gloria Adkins, Linda Dunmire, Diane Adkins. Circa 1950

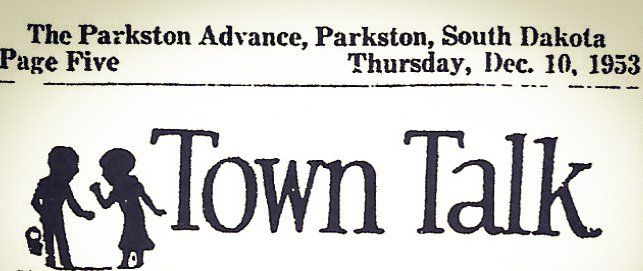

The “Town Talk” section of the Parkston Advance Newspaper reported holiday gatherings so your friends and everybody else in Parkston knew what you were doing and with whom!

Every year, for many years, my mom, Margaret Mize Adkins, roasted a goose for Christmas day dinner, along with pheasants that my Dad had hunted.

The adults loved the goose. I don’t think I ever ate it. Mom had all the trimmings, plus mince-meat pie, which I never ate either.

I must have eaten something though, it was all over my shirt in this Christmas picture!

L-r: Gloria, Kay and Diane Adkins. Circa 1952

In the 1950s, Parkston was home to numerous churches. On Christmas Eve, I could hear all of their bells.

The closest one rang at the Presbyterian Church, our church, just down the hill from where we lived.

It was the smallest congregation in town, comprised of a few families, the Idema’s, Mogck’s, Hayne’s, Shield’s, Wingfield’s and a band of the Mize’s, Mattas’ and Adkins’, my maternal and paternal relatives.

They came on Christmas Eve to watch a young generation perform old pageants and songs.

Presbyterian Church Steeple and bell. Circa 1950s

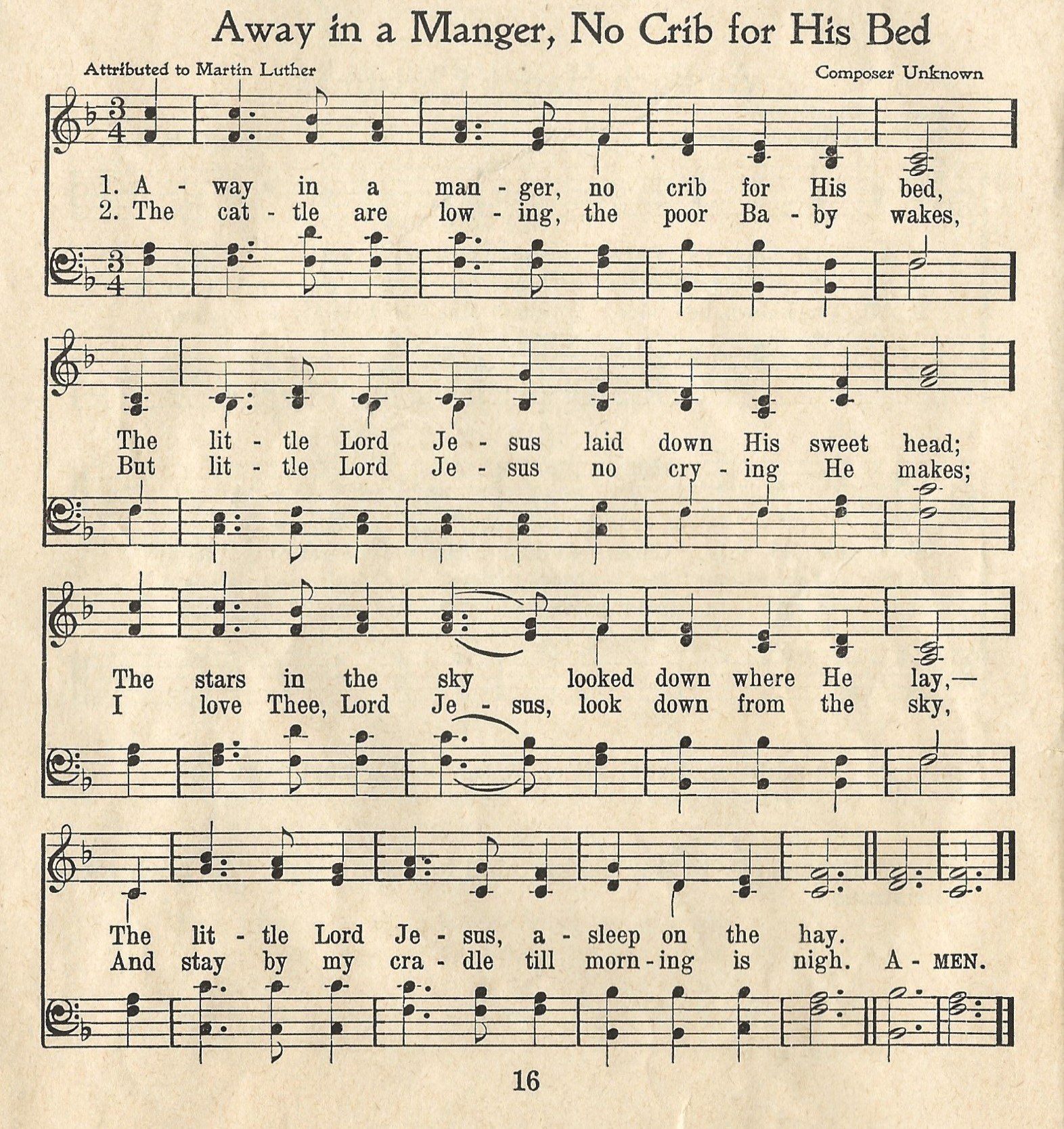

I might have been about four when I sang, “Away in the Manger.”

And several years later, I had to memorize a part.

What I remember most is feeling the magic that seemed to happen in that little church. Perhaps it was the “good will” shared by the people there. That kind of magic never goes away.

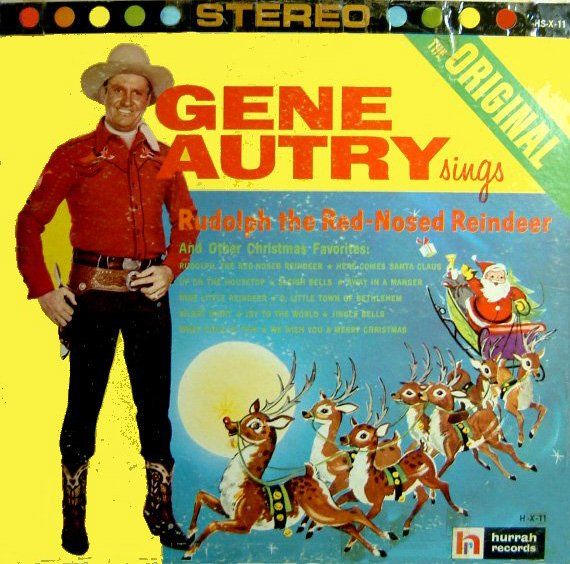

Besides the carols, the sound of other songs brought joy in the 1950s, “Rudolph, the Red Nosed Reindeer” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus.” My Aunt Grace and Uncle George Mattas had a record player. After the Christmas Eve church pageant, to our delight, they would play those records for us.

Grace would also serve us the most divine divinity. Snow white puffs of candy, made mostly of sugar, melted in our mouths.

Grace would also serve us the most divine divinity. Snow white puffs of candy, made mostly of sugar, melted in our mouths.

Grace Adkins Mattas. Circa 1953

Gloria, Kay and Diane Adkins. Circa 1953

At the end of the evening, tired from the pageant, and maybe coming down from a sugar high, my sisters and I snuggled in our coats, ready to go home.

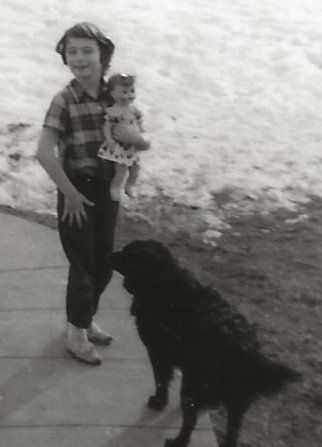

In the mid 1950s, before I had a desire for an electric train, I wanted a doll whose hair was the color of my own. Back then, I didn’t know how scarce money was.

Very seldom was my dad with us on Christmas Eve. As Parkston’s Chief of Police, it was his duty to keep peace that night. He got home in the wee hours of Christmas morning. As a child, I wondered if he ever ran into Santa Claus, who in our tradition delivered presents then.

My dad always tied a set of harness bells to the outside door. They rang with a cheery sound to all those who entered on the holidays.

I remember waking in the night to two sounds. One was a deep voice, “Ho-ho-ho, Merry Christmas,” and the other, the ringing of the harness bells as someone left our house.

I thought I recognized the voice. It didn't matter.

The next morning, there was my doll.

Uncle Everett was right. Santa Claus can be anyone. I still believe that.

Kay Adkins, the doll and her dog, Happy. Circa 1955

Happy Holidays, Everyone!