Pheasant Hunting

A South Dakota Tradition

Marie-Lise Beaudin Photo

Over a century ago when my family came to the Jim River hills near Milltown there were no pheasants. The birds hunted were prairie chickens, quail, grouse, and plovers.

In the late 1880s, my great uncles, Joe Jr., William, Steve, and Henry were given 12-gauge pump action shotguns by their Uncle Fred Harvey from Kansas.

Fred had made a good deal of money creating restaurants along railroad routes. The shot guns were state of the art. One of those shotguns remained in the family for years.

Even then, people were aware of the potential economic benefits of bird hunting. By 1888, the Dakota Territory legislature began enacting laws to create seasons for out of territory hunters.

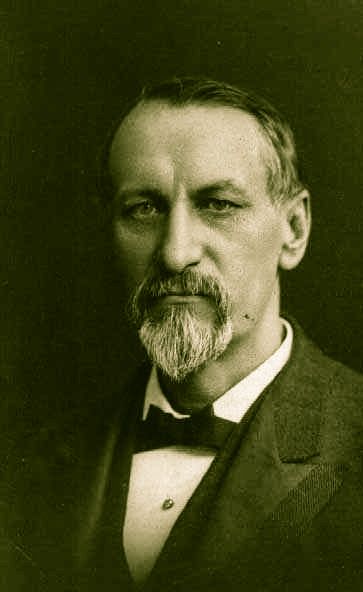

Fred Harvey. Circa, 1880s

Mattas Family at their Jim River home. Circa, 189os

In 1911, the year my father Pete Adkins was born the landscape became a dream for entrepreneurs who believed that South Dakota could become a spot on the national map for bird hunting. What they thought was needed was a highly prized delicacy – pheasants!

The English had been hunting them for years. A native species originally from Manchuria, they seemed well suited for Dakota. In Spink County, up the Jim River from my family’s home, 238 pairs of pheasants were released by the South Dakota Department of Game and Fish that same year.

In 1913, the Parkston Advance Newspaper reported that Game Warden Henry S. Hedrick brought over 5,000 pheasants from a game farm in Chicago. Every county in the state that wanted some got some. By 1919, South Dakota held its first ever pheasant hunt. Though limited to one day and in one county, it was the beginning of South Dakota becoming the “Pheasant Capitol of the World.”

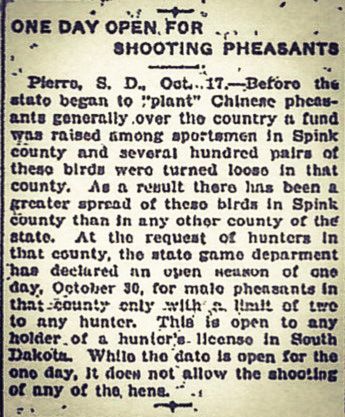

Article from the Parkston Advance Newspaper, 1919

From the time he was old enough until he passed, my father seldomed missed a hunting season.

Photo courtesy of the South Dakota Historical Society.

Through the 1920s, the pheasant population in South Dakota grew to millions. World War I veterans, like my Uncle George Mattas, took advantage of the hunting season that came into existence in Hutchinson County in 1924. He even wore his army boots to hunt!

George Mattas. Circa, 1919

George Mattas. Circa, late 1920s

There were rules, of course, for hunting. Sometimes they were obeyed and sometimes they weren’t! In the 1930s when times were tough pheasants provided a source of food for many families. My mother Margaret (Mize) Adkins told the story of how she and her siblings “hunted” when they were in high school during that time. This is the way I remember it:

“We’d go out at night, and drive through the fields in our old car. It had spotlights on the doors. Some of us would ride on the front fenders, shine the lights into the fields. Sometimes we would blind the pheasants with the spotlights, jump off the fenders quickly, and hit the pheasants with a baseball bat. We usually got enough to feed the family!"

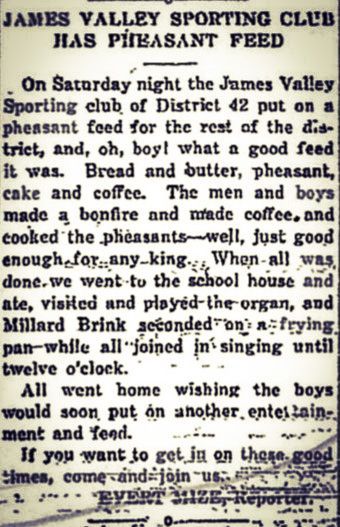

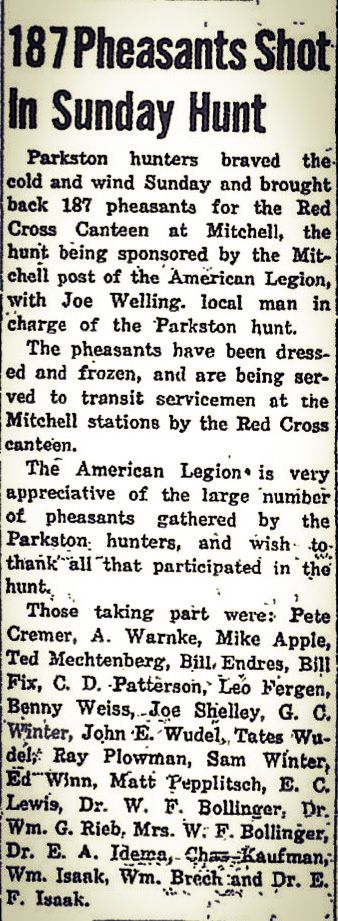

Hunting not only provided food, but was also instrumental in bringing communities together. School District #42, the Stainbrook School District near Milltown, formed their own club – the James Valley Sporting Club.

In 1931, they hosted a wonderful pheasant feed at the school. My uncle, Everett Mize reported on the event in the Parkston Advance Newspaper.

This club was not the only organization to hold pheasant feeds. Others in the 1940s used proceeds from the feeds to help World War II soldiers.

In March of 1945, my uncle, Benny Weiss, along with many others from the community, shot 187 pheasants that were dressed and frozen to be served to transient servicemen at the Red Cross Canteen in Mitchell.

Articles from the Parkston Advance Newspaper

Pheasant hunting brings families and friends together.

When my cousin on the Adkins side of the family, Leo Stirling, was a boy in the 1950s, he remembered going to his grandfather Doc Stirling’s farm to hunt.

“I was 8 or 9 years old, I couldn’t hunt yet, but I would walk along with my cousins and my grandpa’s veterinarian friends from Missouri. When I was about 12 years old, I got my first shot gun for Christmas, it was a four-ten. I took a hunter’s safety course, so I could hunt with them after that!”

L-r seated: Ernest Stirling, Leo Stirling, Missouri friend, Bane Stirling, Kenneth Stirling, Joe Roth Jr., Walter "Doc" Stirling. Others all friends of Doc's from Missouri. Circa, 1950s

Before they could even hunt, my cousins on the Mize side of the family, got involved with the bounty! L-r: Chuck, Jackie and Joe Mize. Circa, 1950s

Chuck Mize remembers going hunting for the first time with his four-ten shot gun in the 1950s, also.

“There would be a bunch of people, sometimes stretching clear across a field. There were Stirlings and McClains and Van Nattas and my dad, Everett. A cattle truck would follow us, and we’d throw the pheasants into it. At the end of the hunt, we would have a fantastic feed!”

Women were not left out of the hunting experience. According to her son, Bill, my great aunt Hazel (Brink) Mattas was an incredible shot.

“She could hit a flying pheasant with her 22-guage rifle. On the farm she would carry it with her when she went to get the mail. A pheasant would come up, bang, dinner! This was in the late 30s.”

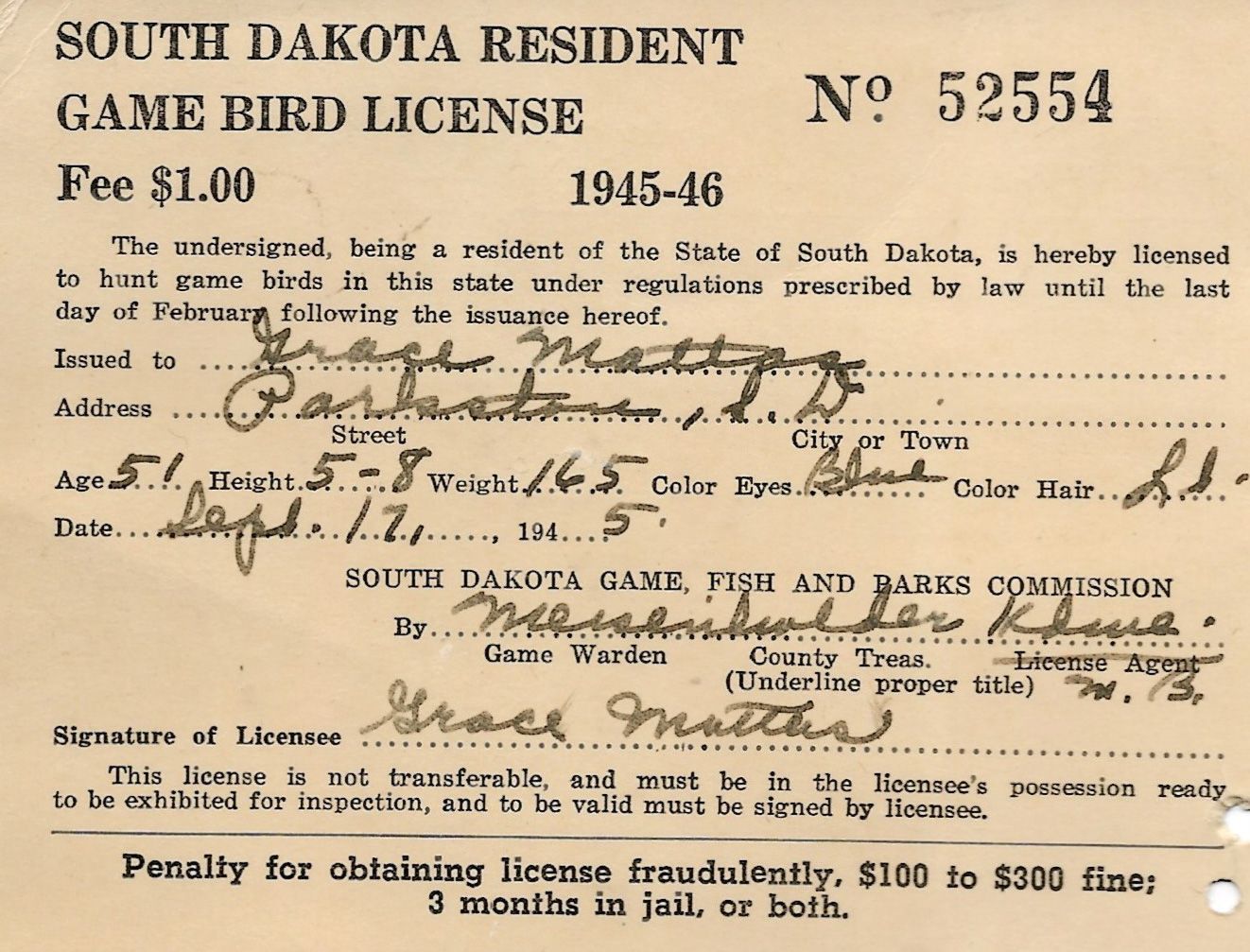

My aunt Grace (Adkins) Mattas had hunting licenses in the 1940s. I don’t know if she ever shot a pheasant or just went along to up the family’s daily limit!

Hazel Mattas. Circa, 1920s

LaVae (Rauscher) Marquardt, my cousin, started hunting with her father Martin Rauscher as a little girl in the 1940s. She would just ride along with him and be a “spotter.” After she married her husband, Roger, she hunted with a four-ten. They would walk along the shelter belts in the late 1950s.

By 1958, there were an estimated 11 million pheasants in South Dakota.

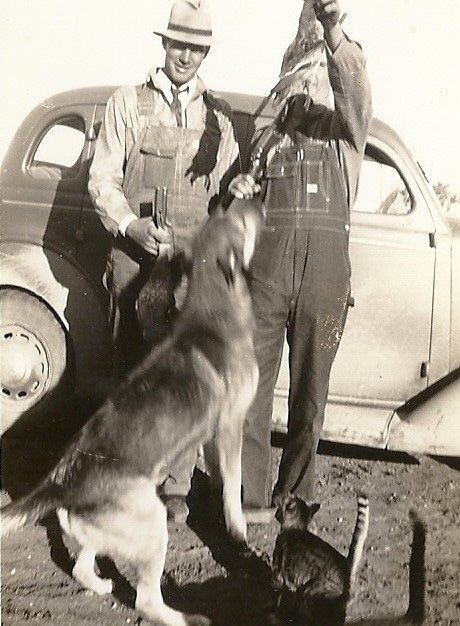

L - r: An unidentified friend with my uncle Martin Rauscher. Circa, 1940s

Most of the pheasant hunting experience for women in those early years was the cleaning and preparing the birds for dinner. Removing the shot was a challenge! No matter how well my mother, Margaret (Mize) Adkins cleaned the pheasant, it always seemed that my sister, Gloria got some in her first bite! For all who ate pheasant in those early years, we can relate to the taste of lead pellets! Gloria stopped eating pheasant.

Most of the pheasant hunting experience for women in those early years was the cleaning and preparing the birds for dinner. Removing the shot was a challenge! No matter how well my mother, Margaret (Mize) Adkins cleaned the pheasant, it always seemed that my sister, Gloria got some in her first bite! For all who ate pheasant in those early years, we can relate to the taste of lead pellets! Gloria stopped eating pheasant.

L - r: Margaret, Gloria and Pete Adkins about the time Gloria stopped eating pheasants! Circa, 1950s

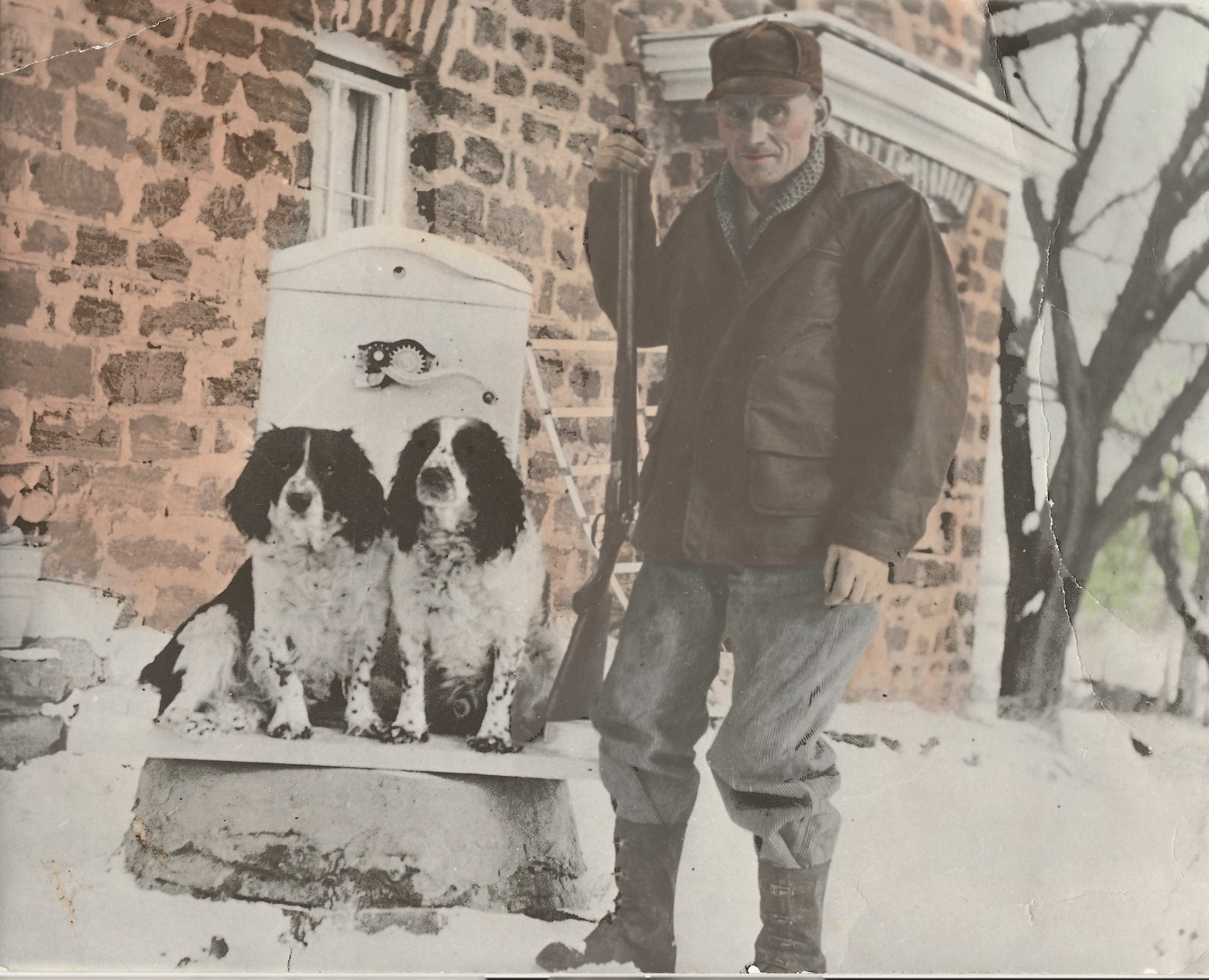

Hunting dogs were not common in those early years. But for some, luck brought them a good dog. Great uncle Steve Mattas had Rough and Rowdy pictured here on the Mattas Place, near Milltown in 1938.

My cousin Chuck Mize had a labrador named Pal. He told this story:

“My dad (Everett Mize) and I would road hunt. Pal would ride in the backseat. After we shot a pheasant, Pal would jump out and retrieve the bird. We’d open the trunk of the car and Pal would drop the bird in the trunk. Away we would go for another pheasant.

One time the bird wasn’t quite dead and the next time we opened the trunk- swoosh- the bird was gone!”

Chuck Mize holding Pal. Circa, 1950s

My dad, Pete Adkins, never had a hunting dog. I had a dog back in the 50s, he was a cocker spaniel. Called him Happy. One day my dad decided that he would take Happy hunting. It was a beautiful October day, and Dad left the car windows open. They stopped by a good field, Happy ran out into it enjoying the run and scared a pheasant up. My dad shot. Happy froze, then ran back to the car, took a giant leap through the open window, and began to howl. The dog was not a happy hunter.

Phot0 of a field near where my dad used to hunt.

My dad did have an opportunity to hunt with a good dog, Sam. Sam was a Britany spaniel that belonged to his future son-in-law, Russ Leonard. Russ tells this story:

“One time out hunting, Sam, scared a pheasant up. The pheasant got its neck caught in a bit of brush on the ground. Sam froze, right behind the caught pheasant and remained there until I could get to it. Didn’t have to shoot that one! We would take the pheasants home to your mother, and she would clean and cook them. They were really good eating.”

For a “really good” pheasant recipe go to Pheasant Parisienne

L - r: Russ Leonard, Sam, Pete Adkins and his brother Steve. Circa, late 1960s

One shared memory is the sense of ritual. That time in South Dakota when the smell of fall permeates the air and there is excitement about relatives and friends coming to hunt. My dad was often relied upon to be a guide because he knew the farmers and the best places to hunt.

There was a sense of pride in him, Diane recalls, as he cleaned his guns. Gloria remembers him meticulously laying out his boots and vest the evening before the season opener, all part of the ritual.

Pete Adkins and an unknown friend. Circa, late 1930s.

Pete Adkins. Circa, late 1940s

My dad, Pete Adkins taught my brother Jim how to shoot. He never taught us girls. It was a different time back then. But that doesn’t mean we did not have the pheasant season experience.

Sister Diane Graber: “When I was eleven years old, my dad took me along road hunting. I had to drive the car. Learned how to stop and go with an old straight stick!

In high school I went with two of my friends. The car we were in had a bench seat, I sat in the middle. My friend in the “pilot” seat had his gun pointed to the floor. He thought he was smart, clicking the trigger. Not too smart, the gun went off and blew a hole in the floorboard! I’m lucky he didn’t shoot my foot. Dad of course was not pleased with the carelessness.”

Sister Gloria Leonard: “We would road hunt with him, be a spotter. I just liked being with my dad.”

In 1919, the first official hunting season, there were a reported 100,000 pheasants in South Dakota. Ten years later, in 1929 there were an estimated 4 million. Those early entrepreneurs made an excellent decision by importing the birds, the wily ring-necked pheasant really took to the landscape! Good hunting for my uncle George Mattas!

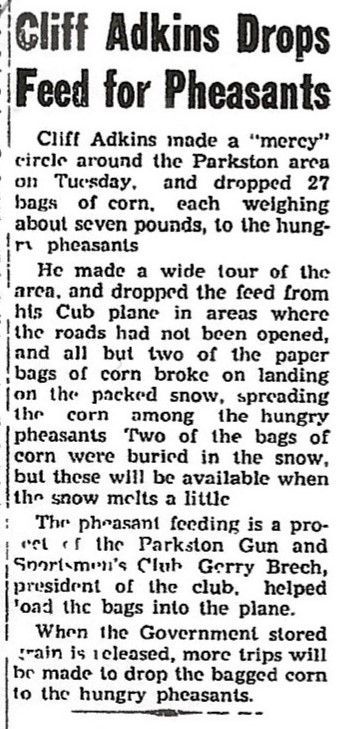

Over the years, the pheasant population has fluctuated, reaching a peak in 1945 with 16 million birds and a low in 1976 with only 1,400,000. At times residents stepped in. In 1942, my cousin Cliff Adkins flew his airplane to drop feed to starving pheasants.

George Mattas. Circa,1930s

From the Parkston Advance Newspaper, March, 1962.

Today, the pheasant population is holding steady at 7 million. That includes over 800,000 pen reared birds that are released every year. An estimated 122,000 hunters, 70,000 of which are non-residents walk the landscape in hopes of bagging our State Bird.

Howard Mattas. Circa, 1991

My great uncle Henry Mattas, who got his first shotgun in the late 1880s, passed his love of hunting to his son, Howard. After Howard moved to Nebraska, he would still come back to South Dakota to go hunting.

Henry Mattas, Circa 1920s

Howard Mattas holding the 1934 gun. To his left, son, Martin. Circa, 1985

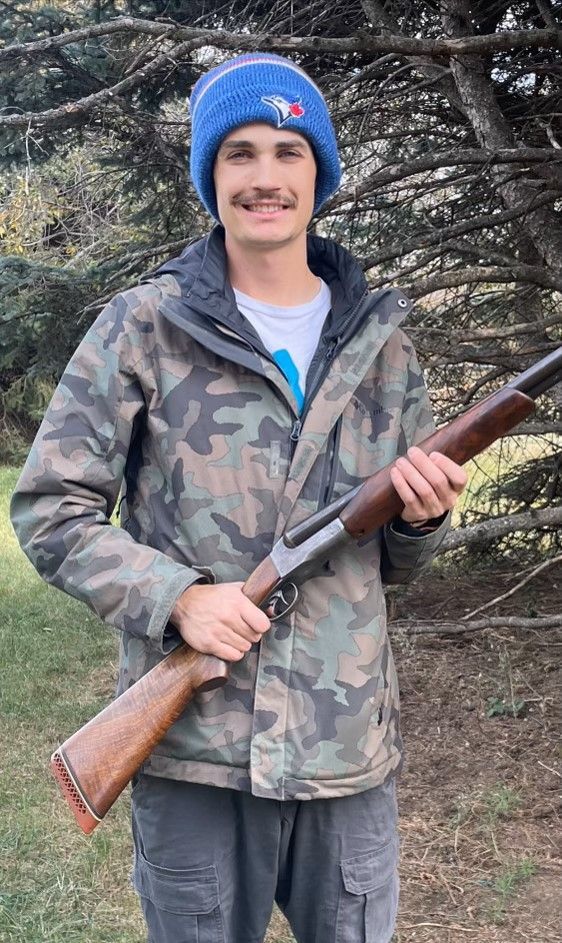

Wayne Mattas, holding his grandfather Howard's gun.

Circa, 2023

Steve Mattas, Howard’s son, shares this story:

“Grandpa Henry would take my dad to school in the 1930s in a horse drawn wagon. Grandpa would shoot pheasants going to and coming back. Sometimes he would get a lot of pheasants!"

Steve continues with this story:

“On my father’s 8th birthday in 1934, Henry gave him a double barrel shotgun. My father hunted with this shotgun his entire life. He gave it to me in 1998 with the understanding that the gun would always be passed to a Mattas. I gave it to my nephew, Wayne, who still hunts with it.”

For over a 100 years our family’s pheasant hunting tradition continues!

My cousin Bill Hoffman raises pheasants and releases them. This year he released over 275. He doesn’t take any money for guiding and allowing hunters on the land. He does it in the spirit of our family’s tradition. Spreading camaraderie and gathering friends and family together. Bill says this year, he has seen a lot pheasants! He believes it will be the best crop since the 1960s. Happy hunting, everyone!

Statistics sited in this story came from the South Dakota Department of Game and Fish. Special thanks to Leo Stirling, Chuck Mize, Russ Leonard and Dr. Steve Mattas for sharing their pictures.